Weather, Wind, & Wildlife

Forests Have Reclaimed the Adirondacks

If you faced north from the summit of Whiteface at the end of the 1800s, you would be looking at a landscape filled with patchy parcels of stumps as far as the eye can see. In that era millions of logs were cut and floated out of the region on rivers. As a result, forest fires became widespread, and runoff from over-logged areas polluted the water supply for cities downstate. These concerns led in 1892 to the formation of the Adirondack Park, one of the first well-protected ecosystems on Earth. Logging is still an important part of the economy in the Adirondacks, but it now occurs on a smaller scale on private lands. State protection and new logging practices have allowed the forest to recover.

A Frozen Name

Why Whiteface?

Whiteface is unusual in the Adirondacks because it stands alone. That’s part of the reason for its name – because in winter a glazing of white attaches itself to the mountains upper reaches.

On cold nights, when the wind blowing on Whiteface is just a breeze, the trees and structures on the mountain can actually be colder than the air. As the wind wafts by, the moisture in the air hits the cold surfaces, and like your breath blown onto a winter window pane, it turns to frost. That coating of crystals is why Whiteface’s extra white peak often appears to shimmer in the winter sun.

A World Wide Wind

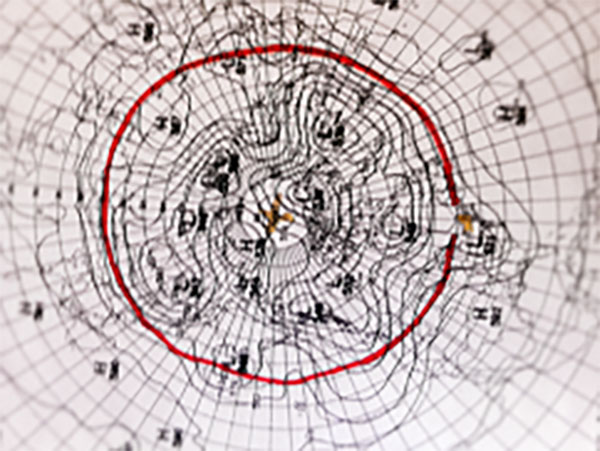

One reason Whiteface is such a hard place to live is the wind, which can blow as fast as a major hurricane or typhoon. The picture here shows the North Pole in the center, the red line marks high elevation winds that can blow around the whole world before smacking into Whiteface. It’s also the reason the mountain is home to measuring equipment that can detect pollution from across the Pacific ocean.